When my maternal grandmother passed away in the mid 1970’s several weeks were spent after her death clearing up various affairs at her long time residence in Potchefstroom. It was at this time that I came to the realization that some forty years before the start of the second world war and the systematic extermination of various ethnic and religious groups of people, the British had in fact started their own private war against defenseless civilians – during the second Boer war.

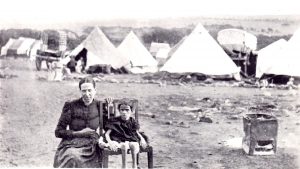

British commander in chief, Lord Kitchener would exhaust the Boers by devastating the farms that had sustained the Kommando by exercising a so-called “scorched earth policy” placing women and children, both black and white in concentration camps.

Kitchener also built a formidable line of blockhouses that bisected the countryside and started flushing out the Kommando in a series of systematic drives with success defined in a weekly “bag” of killed, wounded and captured.

Several items were recovered as part of the estate wrap up, among them some old pieces of home-made soap wrapped in paper and labeled ‘konsentrasiekamp seep’.

Several items were recovered as part of the estate wrap up, among them some old pieces of home-made soap wrapped in paper and labeled ‘konsentrasiekamp seep’.

I remember seeing these acrid smelling large blocks of yellow soap and apparently they were donated to some museum. Another item that was recovered was a pin fire small calibre personal revolver with a folding trigger and octagonal barrel.

Somewhere in time this too has disappeared into the wide world, though they’re not very valuable, this particular item carried the reputed legacy of having been taken into the concentration camp by my great grandmother during her internment. It was in the concentration camp that my grandmother was born in 1900.

Boer families were corralled in concentration camps by the British during the second Boer War from 1899 to 1902. You can read in depth details in Dr Ken Baker’s well written blog post for schools and meta-site for History students GCSE through A Level entitled Analysing “Empire”: the Boer Camps but I’ll provide some key facts here.

The first of the camps which were labeled refugee camps and were established to house the families of families who supposedly surrendered voluntarily. Of course families of Boer kommando members were were driven off the land and forced into camps established all over the country.

The first of the camps which were labeled refugee camps and were established to house the families of families who supposedly surrendered voluntarily. Of course families of Boer kommando members were were driven off the land and forced into camps established all over the country.

The conditions led to the death of over 4,000 women, over 22,000 small children and over 1 600 men. The men were not considered ‘prisoners of war’ since many of them were elderly or infirm. Every able bodied man and some women, joined the Kommando to defend the land against the British.

Several empathic parties like Emily Hobhouse who wrote The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell (London, Methuen, 1902) and Johanna Brandt van Warmelo tried to elevate the profile of the plight of the Boer, especially the women and children in the camps. Interestingly, the British also created camps for indigenous black Africans also but they isolated them from the white Boer families.

Kitchener’s troops destroyed 30,000 farm houses, torched dozens of towns and interned almost 120,000 Boers, a quarter of the population.

Claiming “It is for their protection against the Kaffirs” the British War Secretary told parliament hiding the fact that black Africans were being armed and encouraged by the English to attack what they positioned as a mutual enemy in the white Boer.

Claiming “It is for their protection against the Kaffirs” the British War Secretary told parliament hiding the fact that black Africans were being armed and encouraged by the English to attack what they positioned as a mutual enemy in the white Boer.

They also ignored the fact that 115,000 “black Boers” were sent to their own concentration camps, cohabitants of Boer farmsteads and loyal servants (not slaves or indentured) who saw twelve thousand of their own number die in camps.

In late 1900 an anti-war South Africa Conciliation Committee read about the camps, they started to collect clothing, blankets, and money for the camp inhabitants and organised themselves into the separate South African Women and Children’s Distress Fund.

Emily Hobhouse was a member of the Distress Fund and sailed out to the Cape in January 1901 with the goods and money, to distribute clothing and food among camp inhabitants on behalf of the Fund. Hobhouse, who had no parents and no husband, was a natural choice.

Hobhouse was not the only Briton to report on what was happening. Quakers – Joshua Rowntree and George Cadbury described what they saw and their words were reported in the British press. Both were careful not to blame specific people for conditions in the camps.

In March of 1902 a report of the Ladies Commission (Fawcett Commission) on the concentration camps was discussed in the House of Commons. War Secretary St.John Brodrick appointed suffragist Millicent Fawcett to assemble the committee of women to go out to South Africa to investigate the camps and initiate reforms.

The Commission concluded that there were three causes of death in the camps

- Unsanitary conditions

- Causes within the control of the inmates

- Causes within the control of the administration

The Opposition tabled a motion deploring the “mortality in the concentration camps formed in the execution of the policy of clearing the country.” Joseph Chamberlain then Colonial Secretary defended the position stating that it was the Boers who forced the policy on Britain and the camps were an effort to minimise the horrors of war. The Opposition motion was defeated by 230 votes to 119.

Toward the end of the month the Aborigines Protection Society highlighted the fact that the Ladies Commission (Fawcett Commission) had ignored the plight of blacks internees in similar concentration camps and wrote to Chamberlain requesting a government inquiry and stating that something should be done “as should secure for the natives who are detained, no less care and humanity than are now prescribed for the Boer refugees”.

Toward the end of the month the Aborigines Protection Society highlighted the fact that the Ladies Commission (Fawcett Commission) had ignored the plight of blacks internees in similar concentration camps and wrote to Chamberlain requesting a government inquiry and stating that something should be done “as should secure for the natives who are detained, no less care and humanity than are now prescribed for the Boer refugees”.

On the request Sir Montagu Ommaney, permanent under-secretary at the Colonial Office, later is reported to have decided that it was unnecessary “to trouble Lord Milner … merely to satisfy this busybody”.

At its peak, over 115,000 women, children and men were in British concentration camps in South Africa. Other camps were set up in St Helena, India, Bermuda and Ceylon. In mid 1902 the Transvaal republic folded its defensive position against Britain. Acting President Schalk Burger of the ZAR (South African Republic/Transvaal) was quoted to have said”… it is my holy duty to stop this struggle now that it has become hopeless … and not to allow the innocent, helpless women and children to remain any longer in their misery in the plague-stricken concentration camps …” You can read more on this here.

I am not entirely sure when the family were interned in the Potchefstroom camp where 1278 were held and 1147 died.

Though the camp likely was established in 1900 – conditions were apparently quite bad like all concentration camps.

Though the camp likely was established in 1900 – conditions were apparently quite bad like all concentration camps.

By August 1901 the camp was moved to a new site on sloping ground with better drainage. At the same time, people were continually moving in and out. In September there were over 600 new arrivals.

Conditions were so inadequate that many people still had to live in the town. At the same time, the deportation to Natal of families whose men were still on the Kommando, began. As late as May 1902, at the end of the war, there were over 1,000 camp inmates living in Potchefstroom town.

My Great Great grandfather – Johannes Hermanus Michiel Kock was mortally wounded at the battle of Elandslaagte on October 21, 1899 and then passed away October 31, 1899 in Ladysmith near what is now KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. His daughter Hendrina was married to Phillip Eduard Malherbe who was captured at Hartbeesfontein in March 1901 and sent away to the Bellary camp near Madras India as a P.O.W.

It is likely the family was rounded up shortly after his capture. 9 months after his capture my grandmother was born in the camp. Phillip returned after the war and died in the mid 1940’s as did Hendrina in South Africa.

Ironically, some sixty years later my mother would marry an Englishman.

Fortunately, none of his family ever had a connection with the Boer War as far as I can tell.